GRAND INDIEN CIRCUS, RECIRQUEL COMPANY & THE STORY BEHIND OF THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY YEAR OF MODERN CIRCUS

HOW CAN A EUROPEAN CIRCUS DIRECTOR CONTRIBUTE TO AN INDIAN CIRCUS TRADITION THAT HAS ALREADY EXISTED FOR MANY HUNDREDS OF YEARS?

By Krisztian Kristof – Ma Directing Circus – Bath SPA University/Circomedia

Invitation and the main concept :

As a creative and circus choreographer for Disney’s live action movie “Dumbo” directed by Tim Burton last year, I worked with three performers from India whose managers invited me to Jaipur, India to work on a new project to establish a new brand, called D&F Bros Grand Indian Circus. In order to make a successful new circus show, I worked together with an English promoter from All Access Areas, a U.K. based company and an Indian producer from Rhythm and Ragas, a company based in Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. The promoter and the producer already worked together from 2014 until 2017 on a unique project called Circus RAJ. Some features of Circus RAJ’s shows are described in this paper to set a benchmark for D&F Bros Grand Indian Circus Show.

The goal, which we originally set up, was to create an independent theatrical circus show and to take pictures and to record videos for promotion. Targeted venues were mainly outdoor events, such as Glastonbury Festival, Camp Bestival in Lulworth and Sziget Festival in Budapest. Furthermore, we wanted to adjust the show to the taste of European audiences and the performances to be family friendly. I certainly faced a challenge as the producer and the promoter had high expectations and wanted to repeat the success they achieved with the Circus RAJ, even hoped to take this circus company a step further with using dramaturgy.

On our first meeting back in the U.K., we agreed on the main parts of the Grand Indian Circus show, to which they could count on my contribution. While the promoter emphasized the importance of reforming the stage set to be safe and more versatile, the producer wanted to introduce theatrical elements in the new show. Moreover, my approach as a European director could help them to determine what kind of show can be appreciated by European audiences, mainly families and children.

For the dramaturgy of this piece, I needed to research on ancient legends from India that I can use for writing the scenes for the show with taking the values and authenticity of the Indian circus into consideration. Finally, I found two suitable legends: the legend of Bhangarh and the legend of Ravana from which we chose the first one for a couple of reasons. Whereas the latter myth is based on Hindu religion (Doninger, 1999), the second one is popular in India and is not so closely related to religion (Tripathi, 2015). Due to the Indian producer’s being Muslim, the legend of Bhangarh seemed a better choice. Additionally, the legend of Bhangarh depicted a more universally understandable story than the legend of Ravana.

Another advantage of this story was that Bhangarh fort is in Rajasthan state, India, from where we were accommodated only 80 kilometers far away so the possibility to visit the place where the legend was born gave us the opportunity to get an insight into the culture from which it came from. I will review the legend in detail in the following section of this essay.

Legend of Bhangarh :

The legend of Bhangarh is a famous myth, which we used as a base for the narrative of the show. The story came from Bhangarh fort, which was built in the 17th century in Rajasthan state in India. According to this legend, a black magician of an old age fell in love with the young and beautiful princess of Bhangarh when she went to buy her favorite perfume at the local market, but she rejected his approach. As a result, the wizard turned to black magic to win the princess’s heart and made a love potion which was able to make anybody, whom it touches, fall in love with the magician. He forced the seller who usually sold the favorite scent to the princess to exchange it with the potion, but he did not take it into account that the vendor was in love with her, too. So, the boy told the princess that the perfume was fake who immediately threw it onto the wall of the fort. The wizard wanted to save the potion and ran towards the wall, which collapsed and buried the black magician under stones. Before he died, the wizard cursed the fort of Bhangarh, which became deserted after the curse in a couple of days.

Today, the fort is still abandoned and is considered one of the ghostliest places on Earth (Tripathi, 2015). People live only in a village around the ruins. When we visited the fort for the first time, what happened to be sensational to me was that apart from tourists only monkeys appeared to be visiting the fort. This experience also contributed to the way I wrote the dramaturgy, which I will specify later in this essay.

The tradition of ancient Indian circus: Kalbelia gypsies :

One of the targets we all agreed on was that the performance we created had to remain traditional in order to ensure its uniqueness and authenticity that might be interesting and attractive for European audiences. When I arrived in Jaipur and began to conduct castings, I got acquainted with the Kalbelia gypsies from which tribe performers arrived to be rehearsed. So as to catch the essence of the authenticity of ancient Indian circus, I started to do research on this tribe which occurred to have a circus tradition for more than hundreds of years.

The Kalbelia tribe served as a good starting point for my research as according to Miriam Robertson their “traditional occupation was snake charming and until about forty years ago they were nomadic” (1998, p.2). Robertson says that the nomadic Kalbelia tribe were “moving from place to place with tents and donkeys” (1998, p.10). She also asserts that they were non-pastoral nomads adding that “non-pastoral nomads rely upon human social resources” (1998, p.14). To sum up, Kalbelias earned money with performing snake charming in towns.

Gulabo Sapera was born in 1960 in one of the Kalbelia communities where at that time “the practice of snake charming—catching snakes, keeping them in captivity for extended periods, and training them to perform – has traditionally been passed from father to son” (Srivastava, 2008). Thus, her father was extremely disappointed that he had a baby girl and he ordered Sapera’s mother and her mother’s sister to bury the newborn baby alive. However, due to Sapera’s aunt’s sense of guilt she rescued her before she died and hid her among cobras, the only place where no one searched for her. She lived among the serpents since the animals did not harm her. After a while, her father realized that she was kept alive and accepted her to take part in the snake charming production he earned money with. After banning the ownership of cobras in India with passing the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, many snake charmers lost their job and struggled for survival (Srivastava, 2008). Gulabo’s family was among the ones who were expected to change their occupation in order to make their ends meet.

Nevertheless, instead of changing occupation, Gulabo invented the Kalbelia dance. This dance is described on UNESCO’s intangible heritage webpage as follows: “women […] dance and swirl, replicating the movements of a serpent” (UNESCO ICH, 2010). Because of the Kalbelia dance, Gulabo Sapera was awarded Padma Shri, a civilian prize in 2016 for her distinguished service in Folk Dance. Not only was the Kalbelia dance referred to as a cultural heritage by UNESCO but they also praised the music, men accompanied the Kalbelia dance playing “the ”khanjari” percussion instrument and the ”poongi,” a woodwind instrument traditionally played to capture snakes” (UNESCO ICH, 2010).

According to Robertson, Kalbelia gypsies settled down in Rajasthan, north of India approximately forty years ago and had to adapt themselves to the new economic situation, so they had to replace some of their financial resources with “begging and other subsidiary occupations” (1998, p.2). According to Raphael Treza’s documentary with the title Cobra Gypsies, which explored the everyday life of some Kalbelia gypsies in the Desert of Tarth in 2015, some Kalbelias became dancers and musicians while other communities developed to pursue hunting, gatherering and a few became nomadic agricultural workers or shepherds. Other Kalbelias did not stop hunting cobras and performing snake-charming despite the Wildlife Protection Act.

Even if nowadays they live in tent villages and have been obliged to change their occupations, the documentary shows us how deeply music, dance and even familiarity with serpents are rooted in their culture so I felt that taking their traditional dance and music into the show is a good decision to create a unique and authentic circus performance. I even had the honour of meeting Gulabo Sapera from whom I could ask for advice about a Kalbelia dancer who can perform in the show (Photo 1).

Photo 1: When I met Gulabo Sapera and her daughter

Circus Raj :

Circus Raj was a unique circus company comprised of Indian acrobats, jugglers, funambulists and folk dancers accompanied by the Rajasthan Heritage Brass Band playing gypsy folk music. This project as well as the Grand Indian Circus was produced and promoted by All Access Areas in collaboration with Rhythm and Ragas in 2014. They toured in Europe from 2015 until 2017 with a show different from what we planned to produce for the Grand Indian Circus brand.

My contribution to the Grand Circus resulted in plenty of changes we applied on the new show, however, I would like to highlight two main differences between Circus RAJ and Grand Indian Circus. Firstly, shows of Circus RAJ lacked any dramaturgy so the performances did not relate to each other and there was no story behind it. For instance, there were moments in Circus Raj’s shows when more than one artist were performing his or her main act on stage at the same time, that resulted in losing the focus of the audience. Another detail we wanted to change was that sometimes only one performer was on stage while the others were waiting behind the curtain to perform. We wanted to modify these features so as to maximize the cultural experience that such a show can give to an audience. Moreover, introducing theatrical elements to the new show and giving meaning to every performance in the show were essential.

Secondly, the main problem with the stage set was the following: if they wanted to perform all types of acts, they had to build two sets. The main part of the stage set comprised of four metal poles and a tightrope that could be constructed by leaning two poles against each other so that they could form two X-shaped structures. Between these frames a tightrope was fixed, and a handful of colorful and patterned textile was hanged on which served as a spectacular background for dancers and musicians and a tight rope for funambulists. Nevertheless, another construction made of a bamboo pole was necessary for acrobats to perform other movements, for example the helicopter act. Not only did they have to build two sets, but they also had to dig a hole to be able to fix the bamboo pole. Hence, assembling the whole set took more time than it should have done optimally. Moreover, bringing a bamboo and four metal poles with all the decorations and other necessary items from India to Europe resulted in high transfer costs that could be decreased by reforming the stage set in a clever way.

Difficulties with casting & cultural transference :

From the problems I faced in India, I would like to highlight three main ones that made it difficult to produce a valuable traditional theatre circus show and to fulfill not only the expectations of producers and promoters but mine also. These difficulties are related to financial issues, Indian business culture and language.

On the first castings from the 12th until the 18th of February 2018 we agreed on selecting nine performers for the show and it seemed that we succeeded to finalise the cast in five days after my arrival. The Indian producers have pre-selected certain artists for casting and rented a small commercial location at Mansarover in Jaipur, which served as a home for the creation and the rehearsal process. Most of the performers who were invited by the producers already toured in Europe with Circus RAJ, except for two young circus acrobats who arrived from New Delhi, who could strengthen the altogether skill of the cast.

On the 4th of March, the cast was still comprised of the same artists we selected in the middle of February who were the following: Lal Bai in the role of the black wizard, Mungharam as the wizard’s helper, Doliya as the princess, Mukesh and Shekhar as the princess’s guards, Govinda as the vendor, Bansi in the role of princess’s servant and two musicians called Vishnu and Omnath. We already started to rehearse when the cast had to be changed for unexpected financial and personal reasons. The number of cast had to be decreased from 9 to 7, so from the 8th of March I could work with two artists less than before. As a result, I needed to change the structure of the cast and eliminate some roles from the show.

Another problem occurred concerning the casting due to an event that can sound quite strange and unknown to European people. I had the great opportunity to select Mungharam, a 42-year-old man, an impressive wonder of nature, who is less than 3-feet-high being perfectly proportional for the role of the wizard’s helper (Photo 2). I considered him not only an eye catcher, but also an iconic figure to build a show on. After weeks of training and rehearsals, his mother finally forbade him from performing in the show. She raised concerns about his delicate health and did not want him to live in the UK for an extended period under difficult working conditions.

Photo 2: Mungharam in the role of the wizard’s helper

Apart from losing him, there were other changes, mainly for financial reasons, I had to get accustomed to. As the budget of the production was never revealed to me, I was not able to incorporate this factor into my desired choices and decisions. Finally, Bansi was out of the show as well as we had to replace both musicians with other ones. I had to be regularly in dispute with either the producer or the promoter over the cast because sometimes they preferred to employ someone with lower-level skills for less money than to work with a professional but a more expensive artist.

I had difficulties not only with the changes I had to apply on dramaturgy and rehearsals but also the Indian business culture was somewhat unknown to me. For instance, it turned out that even if we agreed on working with someone yesterday, it did not mean that we would insist on that agreement the next day, too. Agreements and promises seemed volatile to me in India that caused several problems with the creative process.

Finally, language boundaries occurred to be problematic, too. Although, the producer and the promoter spoke English, hardly any artists could speak another language than Hindi. Therefore, the Indian producer had to translate my instructions to Hindi which did not seem to be as a successful method of communication as I expected it to be. Lo and Gilbert addressed this problem in their essay in which they asked the following questions. “How linguistic translations are conducted and whose interests they serve”? and “Does the translator function as a negotiator or a type of “native informant”?” (2002; p:46). I could not decide whether his translations were distorted because of differences in our interests or simply due to language misinterpretations, I had to find another way of communication at the end to express what I want.

Critical perspectives on intercultural projects :

Originally, we had the intention of getting the best parts from cultures in terms of artistic production, e.g.: dramaturgy and technical competence from Western culture and authentic, tribal art from a non-Western culture, but we ended up conducting rather an imperialistic circus-theatre process. According to Lo and Gilbert though, there is a continuum between “collaborative” and “imperialistic” mode of conducting, along which the technique of a particular show can be placed. They assert that “most intercultural theatre occurs somewhere between these two extremes and specific projects may shift along the continuum depending on the phase of cultural production” (Lo and Gilbert, 2002, p.38). I think we were closer to imperialistic conducting than to the collaborative one.

Imperialistic conducting is the result of an “inequity” that “is often historically based and may continue in the present through economic, political, and technological dominance” as stated by Lo and Gilbert (2002, p.39). Put simple, India is less politically, economically and technically developed than the U.K. Indeed, the U.K. colonized parts of India for several years in the past; moreover, the influence of colonization is still present in India. For instance, I saw that Indian people hold British people in high esteem to an extent that is not the case with other Europeans. This could also contribute to the imbalance in decision-making about the cast or the extent to which we use dramaturgical elements. For example, the Indian producer wanted to place more theatre in the show, like commentaries, but in most cases the British promoter’s requests outbalanced the producer’s opinions.

Lo and Gilbert claim that the imperialistic “intercultural exchange […] is often driven by a sense of Western culture as bankrupt and in need of invigoration from the non-West”, moreover a show produced with this mode “tends to tap into “Other” cultural traditions that are perceived as “authentic” and uncontaminated by (Western) modernity” (2002, p.39). We started this project not because Western culture could not give us any inspiration anymore, but because we wanted to create a unique performance. This means that we were not conducting the circus-theatre in a totally imperialistic way; however, we started to work with the Kalbelias and their culture since we considered them to be left untouched by Western culture and modern society. So, we created a hybrid show by using dramaturgy in a way that this work brought financial potential to the project built on an “intact” culture. For instance, we adopted theatrical elements to a culture, which never had theatre before in order to make a successful show.

What also strengthens the imperialistic attribution of our conducting mode is that imperialistic “form of theatre tends to be product-oriented and usually produced for the dominant culture’s consumption” (Lo and Gilbert, 2002, p.39). That was exactly what we did, but I attempted to implement it in a respectful way. For example, it was one of my goals to have every material and technical element fabricated in the traditional Indian way. The one and only part of the stage set was the two elephant motives appearing on the curtain that had to be laser-printed for the lack of time, but everything else, for example the tightrope and the metal frames were handmade.

Although the method with which we worked on the show was closer to imperialistic than collaborative, we succeeded to produce an integrative intercultural performance at the end. Schechner asserts that integrative intercultural performance can be implemented “based on the assumption that people from different cultures can not only work together successfully but can also harmonize different aesthetic, social, and belief systems, creating fusions or hybrids that are whole and unified” (2013, p.308). I think that we created a balance between cultures in the show, which depicted the “original” culture with some Western contribution while preserving its authenticity.

Schechner acknowledges that all the problems, for example those ones I faced during the one month of production can be viewed from another perspective. He states that all the “misunderstandings, broken languages, and failed transactions that occur when and where cultures collide, overlap, or pull away from each other” can be seen “not as obstacles to be overcome but as fertile rifts or eruptions full of creative potential (Lo and Gilbert, 2002, p:40). If I look at the difficulties from that point of view, the success we achieved at the end of the process was the result of all the problematic parts of the production as well as the easy ones. At the end of the day, exploiting the creative potential of such an “innocent” culture by creating a unique show turned out to be successful in my view.

Strategies to overcome problems

I mentioned a couple of difficulties I had to overcome in India, which were connected to financial issues, Indian business culture, language, stage set and dramaturgy. In this section, I will review my strategies to overcome these problems.

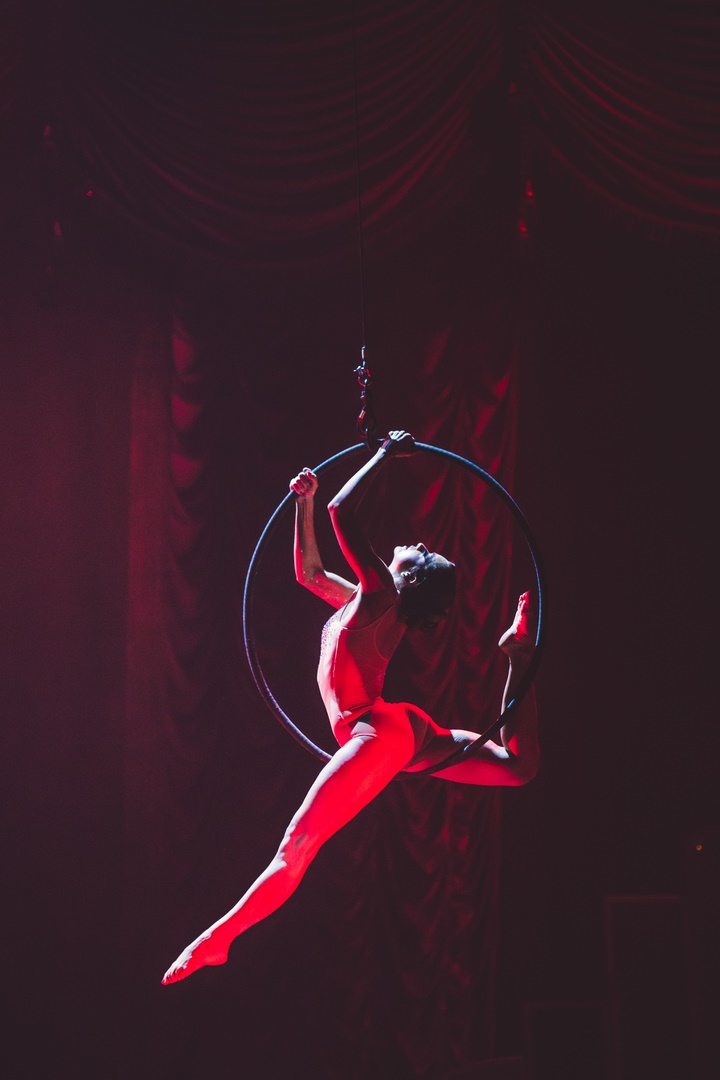

Firstly, changes had to be made on the dramaturgy and the cast for financial reasons in the middle of the production process, on which circumstance I did not have any influence. So, I was obliged to remove the roles of the wizard’s helper and the princess’s servant from the story, and thus I could work only with the roles of the black magician, the princess of Bhangarh (Photo 3), the vendor, the princess’s guards and two musicians. I had to rewrite the scenes I planned for the show, but I think I could solve this problem appropriately.

The strategy I chose to overcome the challenges of the volatility of agreements was to take production notes almost every day in order to be able to show the producer and the promoter the agreements we reached the previous day. Unfortunately, this method was unsuccessful as our compromises were usually influenced by financial issues which seemed to outbalance my requests.

Thirdly, at the beginning of the rehearsals I attempted to count on the Indian producer’s translations so as to make my instructions understandable for artists. This way of communication resulted to be unsuccessful, therefore, I had to show the artists the moves and emotions physically, I expected them to perform. Thus, I could overcome this problem adequately.

Photo 3: Doliya as the princess in front of the Bhangarh fort

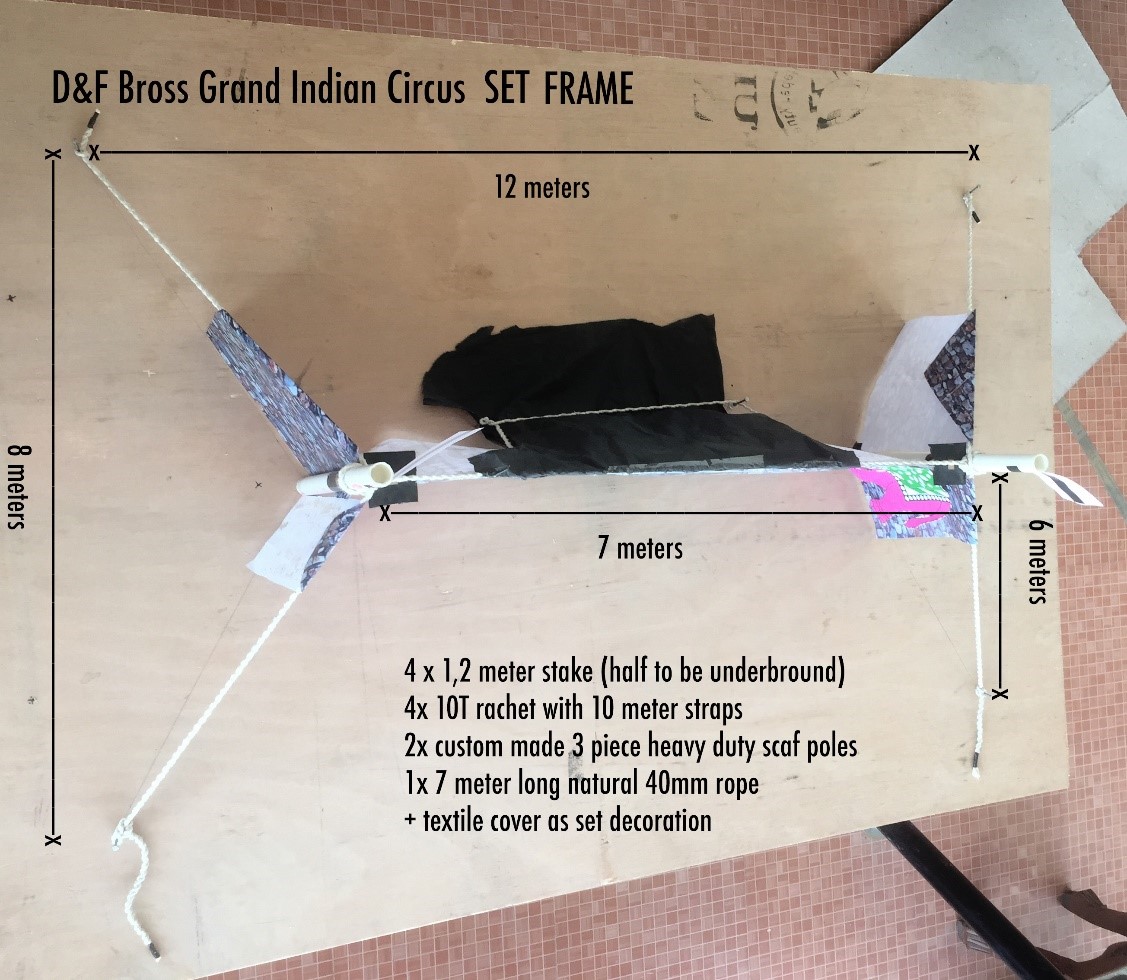

Another challenge of this production was to reform the stage set so that it can be safe and versatile. Our goals with the set were related to aesthetical and technical reconsideration. As far as the technical part of the planning is considered, I redesigned the set of Circus RAJ to stretch only 12 meters and to be 8 meters wide so that it became 6 meters less in length than the original one. Moreover, while the previous set was fixed to the ground only with two points, according to my design it became fastened securely in position with 4 points. Hence, I developed it to be safe and to need less space (Photo 4).

Photo 4: D&F Bros Grand Indian Circus set frame

An additional technical development was implemented on the stage set with introducing modern technology that contributed to the safety of the set, too. We incorporated the use of heavy duty ratchets in order to keep the tension of the rope at a desired level, which were hidden underneath the organic decorations consisting of local flowers normally used for religious Hindi practices.

I also reconsidered the metal and bamboo poles to form one stage set and to be more collapsible and transportable. The new poles were designed to break apart into 3 pieces and to be easily reassembled with using 4 bolts. The resulting pieces did not exceed the length of 150 cm, so airlines could handle them as normal baggage, and the company could avoid paying extra transport costs. Moreover, the acrobatic movements planned for the bamboo pole could be performed on the main set.

From the aesthetic point of view, I achieved to maintain the previously successful colour scheme, which reflected the exotic Indian culture and to depict the fort of Bhangarh. Moreover, a gate to a spacious backstage was formed with the help of textiles in the middle of the set that stood for the entry of the castle. The stage resulted to be intentionally oversaturated in colours so as to be appealing and entertaining for children and families (Photo 5).

Photo 5: D&F Bros Grand Indian Circus final stage set

Furthermore, the technical and aesthetic redesign of the set contributed to the dramaturgical part of the show. For instance, the acrobats suited like monkeys could do the helicopter act on the two poles of the set portraying the “towers” of the fort, which was the reflection of what I saw when I visited Bhangarh fort.

In order to maximize the cultural experience to the audiences, I paid attention to have as many artists on the stage as possible. Furthermore, if a performer did a solo act, I wanted to have the other performers seated in order to avoid losing the focus of the audience. Therefore, I planned a spot on the right side of the stage that stood for a market place, whereas the left side was the place for musicians. In this way, neither the musicians nor the vendor or the guards had to leave the stage during the show. I believe the more performers are constantly visible during the show, the more attractive and spectacular the piece is, especially at open air street festival events.

As regards dramaturgy, I wanted it to form a whole with the set, the story and the skills of the cast. My goal was to work circus techniques into dramaturgy in order to tell the legend of Bhangarh. For instance, Shekhar in the role of the princess’s guard had the skill of extreme flexibility and he could rotate on the ground with a vase on his head. I used his skill to express that Shekhar is holding the love potion for the princess after the black magician hexed him to do so. Consequently, he performed the same act as he could earlier, but a meaning was given to his performance in the show with exchanging the vase with a glass of love potion. With the help of attaching meaning to the performances of the cast, which was apparently related to their skills, the legend of Bhangarh could have been told in the form of a theatre-circus show.

Results :

Despite all the difficulties I had to overcome during the creative process in India, I believe I could contribute to the production with the best of my skills in technical development and dramaturgy. For example, I succeeded to redesign the stage set so that it became safer, more versatile, and more transportable, hence increasing the safety of the show and decreasing its transfer costs and the amount of time needed for the assembling of the stage. Secondly, we created a unique performance with uniting ancient Indian circus with theatre, which resulted in telling a story in the form of a hybrid circus-theatre show. To sum up, I could fulfil not only most of the expectations of the English promoter, but the ones of the Indian producer also. Concerning my own expectations, I think that mainly the deficit in financial support limited the opportunities I could have during production. Nevertheless, I could participate in creating a unique and authentic show, and some artistic goals of mine could also be reached.

On the 14th of March, the last day before heading home, we succeeded to record enough material for a promotion video and take a variety of photos also for promoting reasons. After this hard-working day and the entire month of production, everybody including the artists and the producer seemed satisfied with the results. I could continue working with the materials in Hungary, where I edited a video (Video 1) and promotion photos and sent them to the producer and the promoter. Unfortunately, a new round of cost-cutting was necessary according to the feedback of the promoter. Not only did the budget reduction result in changes that have been made in the show, but the promoter also could not arrange the U.K. work permit for Lal Bai, the black wizard. Because of all these changes, a different show only with five performers started to tour in Europe. Lately, I have received feedbacks from the Indian producer, who was very grateful for the support and guidance I could give them during the one-month production. He also sent me some pictures of recent shows, from which it turned out to me, that they modified not only the cast but the dramaturgy also. Although some dramaturgical features and the stage set were being used for tours, the show became quite different compared to the final one we recorded, and you can watch in the video below.

VIDEO : D&F Bros Grand Indian Circus promotion video

References:

Cobra Gypsies Documentary. (2015). [film] France: Raphael Treza.

Doninger, W. (1999). Merriam-Webster’s encyclopedia of world religions. Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster.

Lo, J. and Gilbert, H. (2002). Toward a Topography of Cross-Cultural Theatre Praxis. The Drama Review, 46(3).

Robertson, M. (1998). Snake charmers. Jaipur: Illustrated Book Publishers.

Schechner, R. (2013). Performance Studies: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge.

Srivastava, A. (2008). New hope for snake charmers. [online] India Today. Available at: https://www.indiatoday.in/web-exclusive/story/new-hope-for-snake-charmers-31264-2008-10-09 [Accessed 1 Aug. 2018].

Tripathi, S. (2015). Bhangarh: a haunting or architectural delight?. [online] Lonely Planet. Available at: https://www.lonelyplanet.in/articles/7763/bhangarh-a-haunting-or-architectural-delight [Accessed 1 Aug. 2018].

UNESCO ICH, (2010). Kalbelia folk songs and dances of Rajasthan. [online] Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/kalbelia-folk-songs-and-dances-of-rajasthan-00340 [Accessed 1 Aug. 2018].

Photos: taken by Krisztián Kristóf

THERE IS NO CONTEMPORARY CIRCUS WITHOUT THE CLASSIC

by Bence Vági, founder and artistic director of the Recirquel company

It is popular to say nowadays that the time of traditional circus is over, the modern man does not need animal performances, we should turn towards more “human” approaches, and forget about elephants once and for all. A small country with great circus traditions thinks differently. The genre of contemporary circus hit Hungarian theatre life in the last few years thanks to Recirquel Company: and Hungarian contemporary circus became internationally acknowledged since. Yet founder Bence Vági returns to the traditional circus roots again and again. As he insists that contemporary circus cannot exist without traditional circus; they have the same origins, and in our times they must learn from and support each other in order to find their own places in the world.

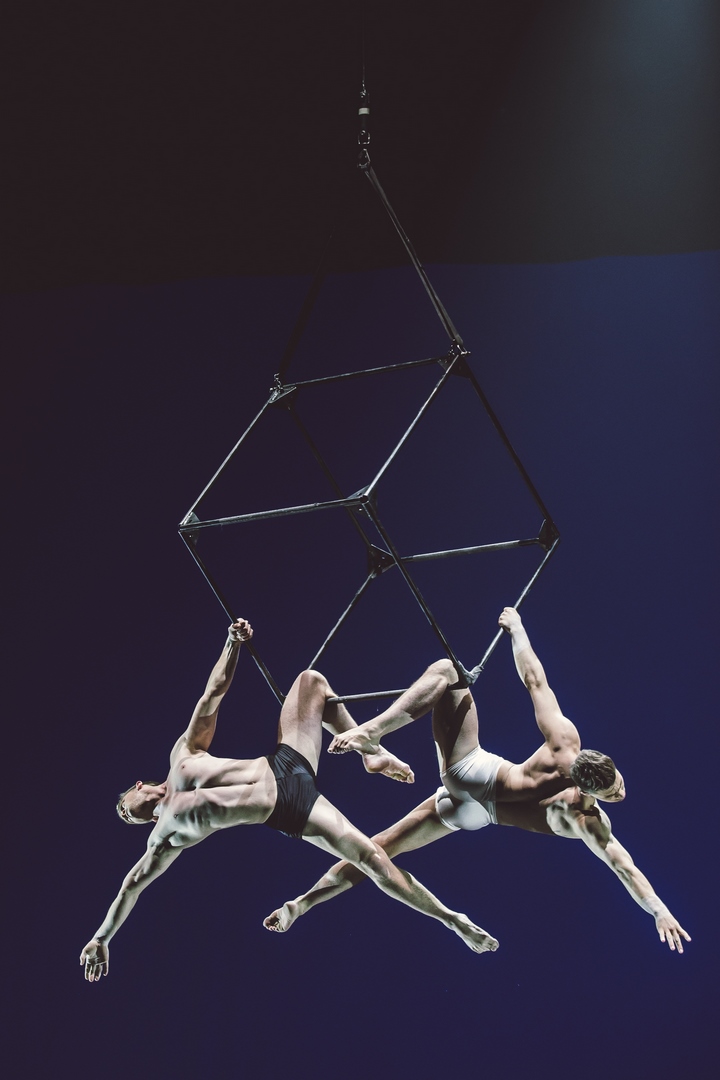

Paris de Nuit, Photo: Attila Nagy, Müpa Budapest

Contemporary circus is a very young genre in Hungary with only a few years behind, while traditional circus has a very serious tradition – the high-quality Hungarian artist training (based on the Soviet school) produced some of the most talented individuals for the world’s circus art. It is no coincidence that Recirquel, the first contemporary circus company in the country that was founded six years ago, has defined itself based on these traditions, having created its very own style, now known worldwide as “Hungarian Contemporary Circus”. One of the most unique qualities of Recirquel can perhaps be found in their respect towards classical circus, and the coexistence of passion for theatre and dance, which comes from the dancer past of artistic director Bence Vági.

Non Solus, Photo: Attila Nagy, Müpa Budapest

Superheroes and Jedi

Despite the commitment to his dancer past and contemporary genres, Bence Vági thinks that contemporary circus cannot exist without knowing and understanding the classical genre. In fact, contemporary circus uses the same ancient techniques to achieve an effect and trigger emotions that characterised the most ancient genre of performing arts a thousand years before. Fear, laughs (clowns), or supernatural powers, the desire to become a “superhero” are present in contemporary circus, just like in cinema or modern-time show business – just think of horror, the Jedi or the genre of comedy.

Contemporary circus and traditional circus are in fact very similar and have the same origins. The change from „old to new” can be primarily seen in storytelling (and not in the absence of animal acts, as many people falsely think). What defines contemporary circus is that the performances are based on dramaturgy, where the story is moved forward in an abstract manner by circus genres and movements.

However, there are many transitions between the two genres, as contemporary circus and traditional circus constantly learn a lot from each other while also inspiring one another. According to Bence Vági, one can find the structures characteristic of traditional circuses in 80 percent of Cirque du Soleil’s performances – starting from the operational model, through the organisation of their tours, to the promotion of the shows.

Paris de Nuit, Photo: Tamas Lékó

Animal acts=mythological wonders

“We wouldn’t be here without traditional circus, so we have to treat it with respect and should never deny it”, says Bence Vági. According to the director, if contemporary circus turned its back on the traditional, it would be like contemporary dance turning its back on ballet. Nowadays, when traditional circus faces numerous attacks for its use of animals, it is especially important that contemporary circus protects and stresses the values of this ancient art form, and that the role of animals is treated in the right place. According to Vági, it is no coincidence that animals are the old companions of circus: animal acts are in fact the representations of mythological wonders, namely the taming of the beast. Its main attraction is again the presence of the ’superhero’ character, before who elephants bow. And these values are important to be preserved.

Animals are given a very special care in most circuses, says Bence Vági. “There are of course bad examples, and animal rights activists are right to act against them, but there are also numerous circuses – such as Circus Krone or Circus Kane – that are exemplary for their treatment of animals”, he added. There are now quality assurance regulations in Europe – such as BIG TOP LABEL – that ensure strict supervision of the treatment of animals for example on the basis of the size and quality of the available space, their diet and how they are trained. By the way, some circuses contribute to the protection of several protected species, as well, the director emphasized.

Photo: Attila Nagy

Elephants in the theatre?

Can we attract classical circus – perhaps even with their animals – to the world of theatre? According to Bence Vági, it is a very exciting question; in fact he is currently working on this possibility with his colleague from the world of traditional circus, Kristian Kristof, at the request of Circus Krone, the largest travelling circus in the world. “We follow our heart here, as we have very strong connections to circus”, Vági said.

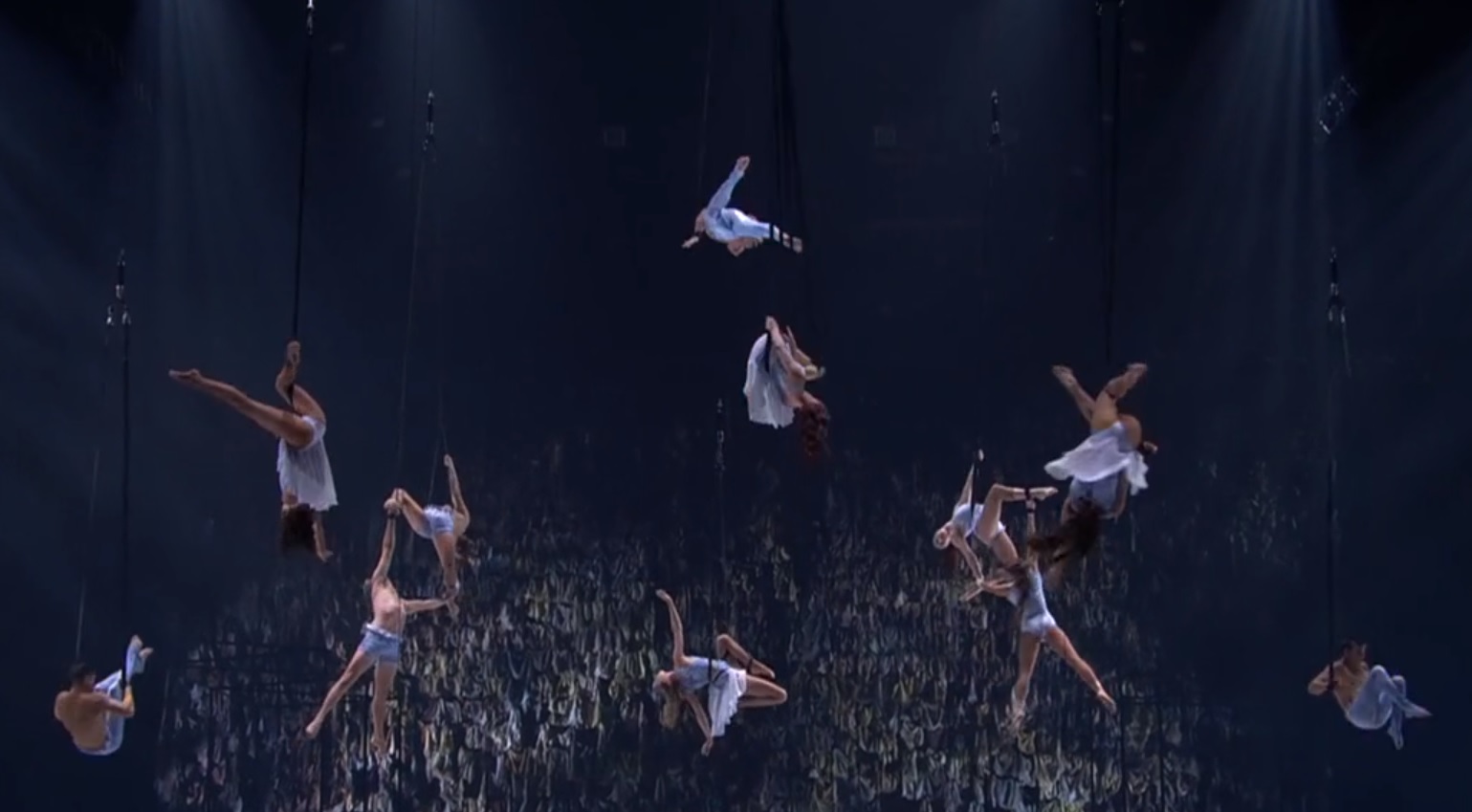

Their effort does not seem to be hopeless at all. The director and his team, Recirquel, have previously tried to combine classical and contemporary circus with great success. The production they created for the Closing Ceremony of the Budapest FINA Aquatics in the summer of 2017 was in fact a circus-ballet performance, where several outstanding stars of classical circus were present alongside hundreds of dancers and acrobats from Hungary and around the world. The concept worked perfectly, representatives of both the traditional and the contemporary circus world acknowledged the production, thus giving a boost to create a new direction. Bence Vági’s new mission is to create a new genre combining dance and circus arts, which he refers to as ’cirque danse’.

VIDEO : Recirquel – Closing Ceremony of the 17th FINA World Championships

THE STORY BEHIND OF THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY YEAR OF MODERN CIRCUS

By Andrew Van Buren, Director Philip Astley Projects CIC

My journey to raising awareness of Philip Astley and his legacy of the circus started with my father Fred Van Buren, who over 80 years ago, as a young boy, saw a picture of an elephant in the local butchers shop, and mistakenly thought they were selling elephant meat! His mother explained it was a poster for Chapman’s circus. He was taken to see it and next the Blackpool Tower Circus, then whilst in school he read about Philip Astley – born 1742 in Newcastle-under-Lyme, just down the road from where dad lived, Astley in 1768 created the modern circus. That was it, dad fell in love with the circus industry.

After a chance meeting with Bob Gandey, dad jumped at the opportunity to join locally based Gandey’s Circus as a performer and never looked back. These events set our family on an amazing journey that would span decades.

Eventually moving to Newcastle-under-Lyme my parents had by now developed their own magic and illusion shows, which took them around the world working in not just circus but also theatre, cabaret and on television.

Then I was born in Newcastle-under-Lyme. I grew up steeped in showbusiness, touring with my parents, learning the business and often with the name Philip Astley being dropped into conversation – we always felt that Astley was lost in history, his achievements fading out of people’s awareness.

Years later, in 1981, dad was contacted by Newcastle-under-Lyme council and asked to advise them on their town carnival. He suggested that the carnival should be themed Philip Astley and circus, but this was greeted by the resounding cry of “who is Philip Astley?” Even here in Astley’s birthplace his name was shockingly forgotten. Thankfully dad’s advice was used and the 1982 Carnival became the first event themed around Philip Astley and the circus. It was a great success, but nobody seemed interested in developing the idea beyond that one event.

Years later in 1990 I realised that 1992 would be the 250th Anniversary of Philip Astley’s birth, surely this was an anniversary that should be celebrated. For a start we felt that there should be some kind of monument to Astley, so dad and I commissioned and funded the making of a life sized statue of Philip Astley, a personally costly thing to do, but oh so important. We thought at the time that this could lead to a permanent monument in Astley’s birthplace and hopefully set the wheels moving on celebrating the man and his legacy.

We persuaded the council to put together a series of events through the summer of 92, the local college put on a circus fashion show, we revisited the carnival idea with a circus parade and shows, the Brampton Museum held a circus exhibition, our ideas were flowing and things were happening at last. It was time consuming and costly for dad & I, but we felt that Astley’s 250th birthday needed to be recognised and celebrated, at least in his birthplace, this could be it, a lasting legacy. Then things began to fall apart.

We tried to find interest and a permanent public site for the Astley statue, but with no luck. Other people realised that the 1992 events would generate an element of publicity and could further their careers, so very soon our ideas were being taken and hijacked, being used for others personal gain. By the end of the year all that dad and I had planned and set in motion happened, but we were cut out of it all, our links to everything erased, credit and recognition went to others, but most importantly this short term mentality and greed had destroyed our long term plans and push for a long term Astley recognition, and benefits to the area into the future.

We reached out further afield, but no interest. Dad and I were devastated. All of our financial investment, ideas and hard work had ended with a summer of events that others took credit for, a statue that nobody wanted and the name of Philip Astley already fading from people’s awareness, nobody else seemed to see any future potential.

Feeling totally used, betrayed and let down, we also had nowhere to store the statue. I even contemplated the idea of it having to be destroyed. Fortunately our very good friends Philip and Carol Gandey stepped in, offering to store the statue – (It was Philips Grandfather Bob Gandey who had started my dad performing in circus).

That was it, in 1993 the statue was moved into a shipping container at Gandey’s winter quarters and locked away. Totally despondent and depressed by the turn of events, dad & I walked away from Philip Astley and the whole idea.

By now my parents had retired and I went on to tour my own acts and shows, occasionally working in circus but mainly in theatre tours, cruise ships, on television and cabaret. I developed my circus skills of trick cycling, juggling and plate spinning, mixing them in with the illusion show, so our ties to circus arts never faded and indeed we have always had a great many close friends in circus, but we had lost heart when it came to Astley and Newcastle-under-Lyme.

After years of working all over the world, my wife Allyson & I realised that we were never at home, we wanted to spend some quality time with our families and to start our own family, so in 2009 I decided that we should for a while perform more in the UK. It was then that I realised that in 9 years’ time it would be the 250th anniversary of Philip Astley creating the circus. How crazy would it be to have a third go at resurrecting Philip Astley’s name and creating some celebrations? After what happened before with the 92 events surely it would be a bad idea! But maybe this time it could be different?

I started talking to people about the upcoming circus anniversary. With Philip and Carol Gandey’s blessing in 2010 I brought the statue out of the container, dusted it down and started exhibiting it. It was loaned to Sheffield Fairground Archive for a three month exhibition, then Gandey’s Circus put it on display at the Edinburgh Festival. Between times I kept it in my studio for visitors to see.

This time I also had a new tool to use – the internet. I started writing about Philip Astley, sharing photos of the statue and shouting about the upcoming anniversary, which most seemed to be unaware of.

Eventually I stumbled across an online conversation about horses in circus and saw that the conversation had been started by an article in our local newspaper, which was about circus history – mentioning everybody apart from Astley! So I commented on it and got into conversation with local Councillor Wenslie Naylon.

Wenslie visited my studio to see the statue. I learned that Wenslie loved the circus and she was amazed to hear the stories about Philip Astley, even remembering the 1992 celebrations. We agreed that the upcoming anniversary should be celebrated and that Astley deserved greater recognition.

I still didn’t really know that many people at home, because of my extensive travelling keeping me away, so the next step was Wenslie setting up a meeting with some key local people to gauge interest.

Over the next few months we spoke to more people, generating local interest in joining our committee, talking to local business, organisations and education providers. Giving more information about Astleys legacy and developing a pride in him. Tackling the animals in circus conversation head on from the start.

The Philip Astley Project was born, which along with Wenslie who chairs the committee and myself with the Van Buren Organisation, consists of other dedicated and hard working groups, individuals and organisations including Staffordshire University – who currently manage the project through their hard working Kat Evans, Newcastle College and Performing Arts Centre, The New Vic Theatre (theatre in the round), Keele University, Staffordshire Film Archive, The Civic Society, Brampton Museum, Appetite, Newcastle- Under-Lyme Business Improvement District, Friends of Brampton Museum and Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council.

The next step was to plan events, research and celebrations of Philip Astley, but realising that it wasn’t just about Philip Astley and his legacy, it was also completing the work my father had started and helping to regenerate Astley’s birthplace of Newcastle-under-Lyme, we felt that Astley and his legacy could be Newcastle-under-Lyme’s “Unique Selling Point”. I coined this with the statement of “if you consider what William Shakespeare has done for Stratford Upon Avon, then what can Philip Astley do for Newcastle-under-Lyme? – Astley is our Shakespeare!” Showing the power of words this has resonated and worked for us.

By now things were moving, Newcastle-under-Lyme council commissioned Philip Astley themed subway artwork. Appetite created the annual “Home-coming” one day festival of contemporary street circus – now in its fifth year.

Kat Evans managed a successful application to the amazing Heritage Lottery Fund, which has enabled us to expand our project on a grander scale.

In 2015 we loaned our statue to the College Performing Arts Centre. Allowing performers of the future to be aware of Astley, a creative pioneer and performer of the past.

Philip Astley Project events and ideas have rolled along gathering great speed and enthusiasm. We started to spread Astley awareness not just locally but also internationally, press coverage gradually grew with articles and stories around the world, all raising positive awareness of Newcastle-under-Lyme born Philip Astley and his legacy of the circus.

Prior to and leading into 2018 we held exhibitions, shows, a season of Circus Films, Talks covering everything from Astley and circus history, to business, clowning and more. We republished an out of print circus book, created an animated film illustrating the history of Philip Astley and his legacy, also in conjunction with Professor Eliene Benicio – the Federal University of Bahia Brazil and Manchester Metropolitan University we held the World’s first Philip Astley Legacy symposium.

We wanted to make sure that all ages, genders, nationalities and beliefs learn about and feel interest and pride in Philip Astley’s inspirational achievements, as a local born man, a war hero, visionary, entrepreneur, builder of amphitheatres, adventurer, showman, performer, the original ringmaster and creator of an art form that has effected so many with his legacy of the circus.

The 250th Anniversary year of 2018 is bigger than we could have ever imagined. Within the circus community there has been and still are celebrations and tributes to this special anniversary.

An amazing start to the year for me was my being invited by Zsuzsanna Mata of Fédération Mondiale du Cirque to attend the Monte Carlo Circus Festival and the unveiling of the Philip Astley Plaque by Prince Albert and Princess Stephanie. After my personal long journey to reach this year it was a very emotional and touching occasion to be a part of.

I was invited by the Association of Circus Proprietors of Great Britain to speak to a parliamentary assembly within the House of Commons, which has led to future possibilities of collaboration with the European Parliament.

After nearly a year of talks, in February, the Realise Foundation, Aspire and PM Training kindly created and set into position the UKs first permanent monument to Philip Astley and his Legacy of the circus – a set of three sculptures of nearly four meters height illustrating the ringmaster plus either side circus horses, as well as a circus big top shaped Welcome to Newcastle-under-Lyme – The Birthplace of Philip Astley sign.

The monument was officially unveiled on the 21st April 2018 – World Circus Day, by myself, Newcastle-under-Lyme Mayor Simon White and Zsuzsanna Mata. This tied in wonderfully with our hosting the closing ceremony of the Fédération Mondiale du Cirque’s inspirational World Juggling Tour film.

Two parallel sets of projects have run in Newcastle-under-Lyme during 2018, feeding from the Philip Astley Project there are over 40 individual circus events and strings to it all, including the Brampton Museum bringing together a collection of original Philip Astley artefacts for their summer exhibition, further talks, film showings, garden displays, shows, school poetry competitions, circus skills workshops, more monuments, AstleyFest plus with the New Vic Theatre’s Circus Past Present & Future there are exhibitions including the Victoria & Albert Museum’s history of circus in photography, conferences, conventions, Astley’s Astounding Adventures play in the New Vic theatre, plus so much more.

We have now set up The Philip Astley Projects Community Interest Company and our plans for the future include developing a centre of excellence for circus arts, history and legacy, research, archiving, plus annual festivals, a heritage trail and more.

People are starting to visit the area to learn more about Astley and his legacy, even travelling from across the world. Awareness of Philip Astley is growing and with it a new appetite for people to attend visiting shows – already this year seven varying styles of circus have visited our area.

We hope that not only will Newcastle-under-Lyme be known as the birthplace of Philip Astley, but also become an ambassadorial home for circus, learning and enlightenment.

For Newcastle-under-Lyme and for the circus industry “Astley is our Shakespeare”.

Andrew Van Buren

Director Philip Astley Projects CIC.